PDFS AND PART OF A TEXT ON THE WEBSITE ITSELF! :3

[DOWNLOAD PDF] "Capital, Containment, and Competition; The Dynamics of British Imperialism, 1730–1939"

[DOWNLOAD PDF] Tsarist Russian Imperialism

[DOWNLOAD PDF] Dynamics of Japanese Imperialsm

[DOWNLOAD PDF] Roots of French Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century; The Case of Lyon

INTRODUCTION ["Capital, Containment, and Competition: The Dynamics of British Imperialism, 1730–1939" by Julian Go, 2014]|

What causes imperialism? The earliest theories came from Spencer (1902: 180–200)

and Hobson (1965 [1902]) who sought to explain Britain’s territorial assaults on

Asia and Africa in the late nineteenth century (Semmel 1993: 103–30). Spencer emphasized the culture of militant nationalism. In Spencer’s view, British society was

undergoing a “re-barbarisation” partly manifest in a jingoist press and parliament. Im-

perialism was the direct result (Spencer 1902: 180–200). Alternatively, Hobson (1965

[1902]) argued that British imperialism resulted from a build-up of excess capital.

Facing underconsumption in England, financiers transferred their capital abroad. They

then pressured the state to annex new territories in order to protect their investments

(Hobson 1965 [1902]: 80). These theories in turn inspired Schumpeter’s thesis of

“social imperialism” (1951) and later Marxist theories of imperialism (Arrighi 1978;

Harvey 2003; Hilferding 1981; Lenin 1939; see Baumgart 1982: 109–11; Brewer

1990; Mommsen 1982; Semmel 1993: 163 for a review).

Considering that the British empire was one of the largest and most influential

empires in the modern world, it is fitting that British imperialism has been the site

of initial theorization. Yet three limitations impede a richer understanding. First, the

Spencer-Hobson tradition overlooks the role of the imperial state. By definition,

imperialism involves state action: the sort of imperialism theorized by Hobson and Spencer, that is, formal (or territorial) imperialism, means that the state declares

sovereignty over foreign territory to make it a colonial dependency. 1 Yet classic the-

ories of imperialism treat the state as little else than a siphon through which other

forces flow, as if the state has no interests of its own. Second, classic theories illumi-

nate the domestic (or “metropolitan”) factors propelling imperial expansion. We get

little sense that the imperial state operates in a wider global system. Finally, classic

theories and subsequent research has been silent on broader historical patterns. The

original theories of Spencer and Hobson focused upon British imperialism in the late

nineteenth century—the so-called new imperialism. Similarly, other studies examine

particular cases of colonial acquisition or specific historical moments but not broader

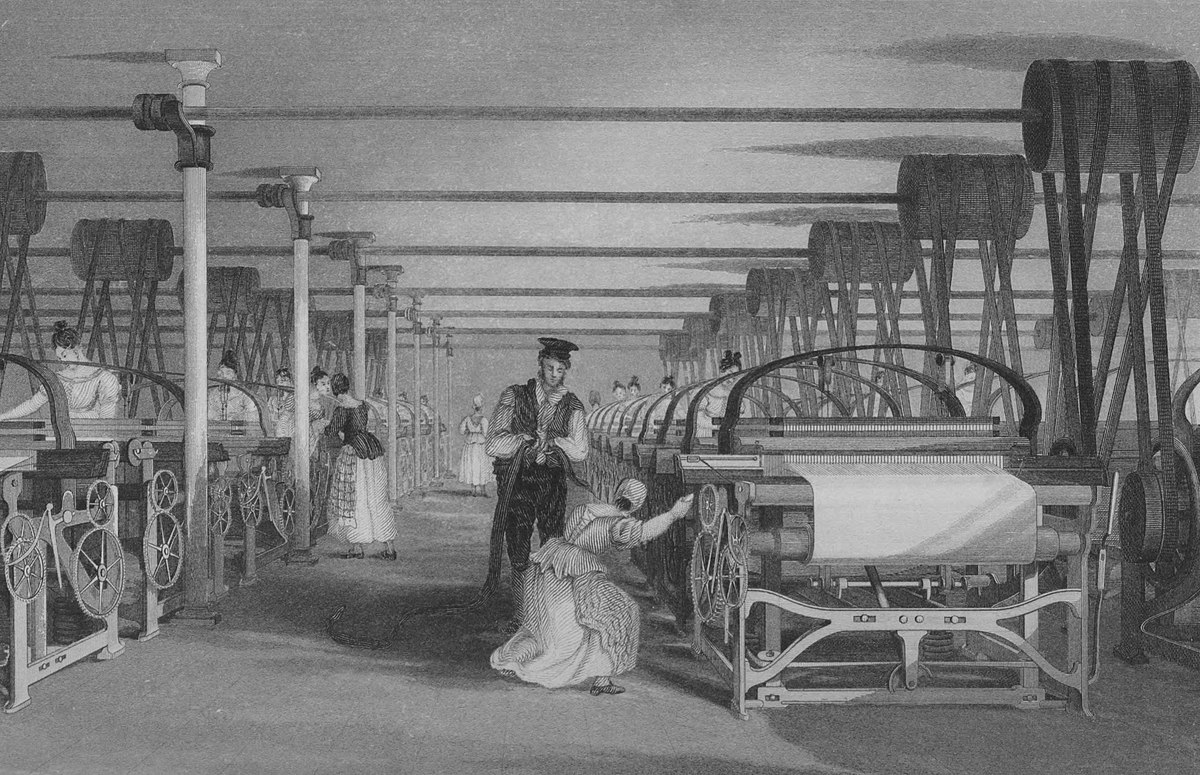

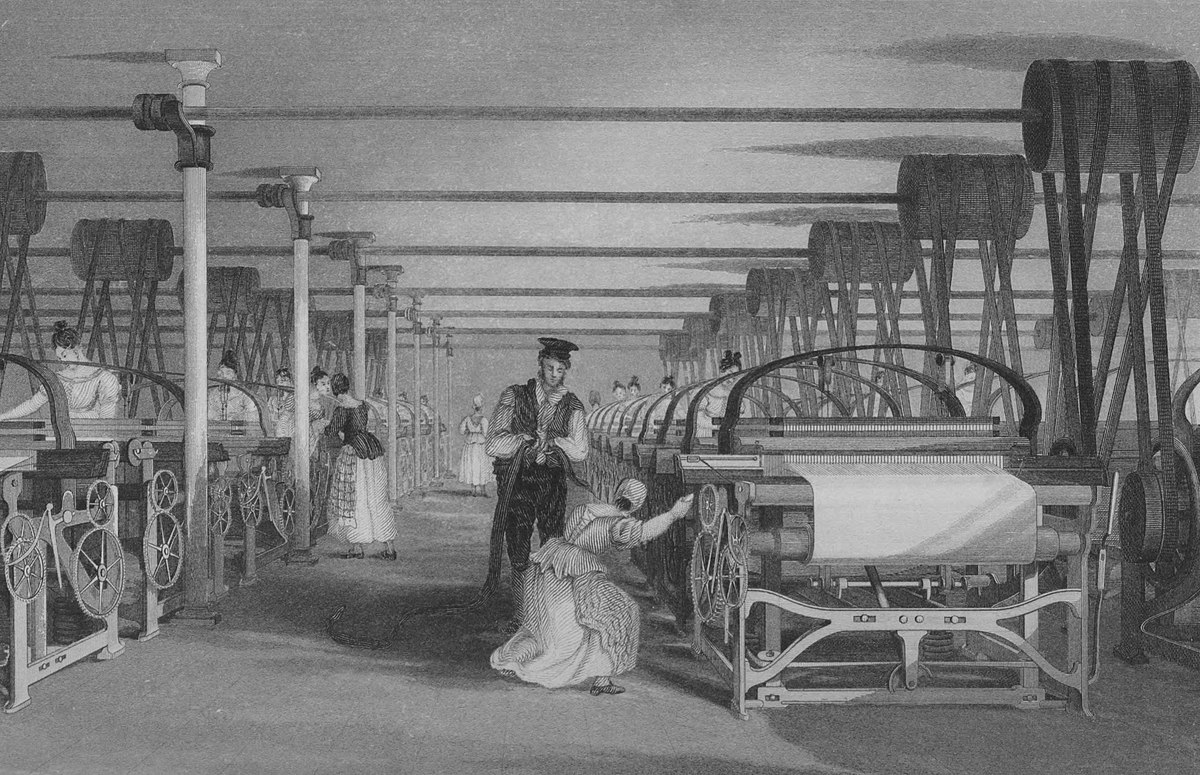

temporal or spatial regularities (e.g., Baumgart 1982). Time-series data on the number

of colonies acquired by Britain shows that British imperialism has had a longer career

than existing theory and research implies (figure 1).

So what drove these imperial dynamics over the long durée? In addressing this

question, the present essay develops an explanation that goes beyond the limitations of the Spencer-Hobson tradition. It shows that British imperialism was not produced

by the ebbs and flows of militant nationalism, nor was it driven by internal economic

requirements or the needs of financiers. It was rather produced by structural compe-

tition. Imperialism was a strategy for meeting the state’s imperatives of geopolitical

security (containment) and economic growth (capital) in the face of external threats.

Such threats were most likely to be perceived when the global system was at its most

economically competitive.

[figure 1]

Theorising Imperialism

The structural-competition explanation induced from the present analysis builds in

part upon various works on imperialism that have already transcended the analytic

confines of the Spencer-Hobson lineage. While both Spencer and Hobson emphasized

domestic causes and overlooked state interests, these other studies suggest alternative

approaches that highlight global factors or state imperatives. The first is a “trade

regimes” approach from world-systems research. This approach has been developed

to explain colonization in the entire world system rather than by an individual state

(Bergesen and Schoenberg 1980; Boswell 1989; Chase-Dunn and Rubinstein 1979;

Pollins and Murran 1999), but it can be adapted to also theorize British imperialism.

This approach suggests that global trade patterns oscillate historically between phases

of free trade and periods of mercantilism (marked by high tariffs and constricted

international flows). 2 Free trade periods mean less colonization because states prefer

open markets. But when free trade declines, states respond with colonization in an

effort to obtain and maintain privileged access to materials and markets (Boswell

1989: 185). Imperialism is a functional alternative to open trading systems (Bergesen

and Schoenberg 1980: 242).

Other approaches include “Realist” approaches such as Realist International Re-

lations theory and variants (including historians’ research). These explanations bring

in global factors while emphasizing state interests. In classic realism, imperialism

is the result of the states’ rational pursuit of interests. All states seek to maximize

power, new territory adds to states’ power, and so states naturally seek new territo-

ries. What determines whether or when states will pursue territory is their capability.

States will expand when they can; that is, when they are militarily stronger than other

states (Morgenthau 1978). Variants of this approach include “state-centered realism,”

which emphasizes internal capabilities rather than military power. States will expand

when they have the organizational capacity to do so (Zakaria 1998). Alternatively,

“defensive realism” asserts that states expand when they must (rather than when they

can); that is, when their security is threatened (Snyder 1991). This latter approach

surfaces in other work too. For instance, some historians suggest that Britain’s new

imperialism was a response to rival’s colonizing activities (Baumgart 1982: 39–42;

Fieldhouse 1973; Robinson and Gallagher 1961). Likewise, Abernathy (2000: 209) characterizes European expansion as “defensive aggression”: European states felt

threatened when other states took territory and so responded in equal measure.

The evidence in the following text yields a different explanation: structural compe-

tition. British imperialism was not the product of finance capitalism or jingoism but

was rather a state strategy to contain threats—geopolitical and economic—that arose

when the global structure was at its most economically competitive. This structural-

competition approach thus partly builds upon the “defensive realism” thesis and

Abernathy’s related theory of “defensive aggression.” But it expands them. Like

these approaches, a structural-competition approach posits imperialism as a response

to external threats. But unlike standard defensive realism, the structural-competition

approach specifies the structural conditions under which such external threats are

most likely to be felt. Abernathy (2000: 9) suggests that European states lived “in a

pervasive sense of insecurity” and seized territory in direct response to other states’

“territorial advances” (209; emphasis added). Similarly, classic International Rela-

tions (IR) theory suggests that threats emerge when rival states take new territory;

France takes Algeria, so England takes West Africa. Baumgart (1982: 40) suggests

that the threats can be “real” or “imagined,” which leaves open the question as to when

states are more likely to perceive such threats. In contrast, a structural-competition

approach suggests that perceptions of threat are most likely to proliferate during

specific historical phases: that is, multicentric phases defined by an economically

competitive global structure.

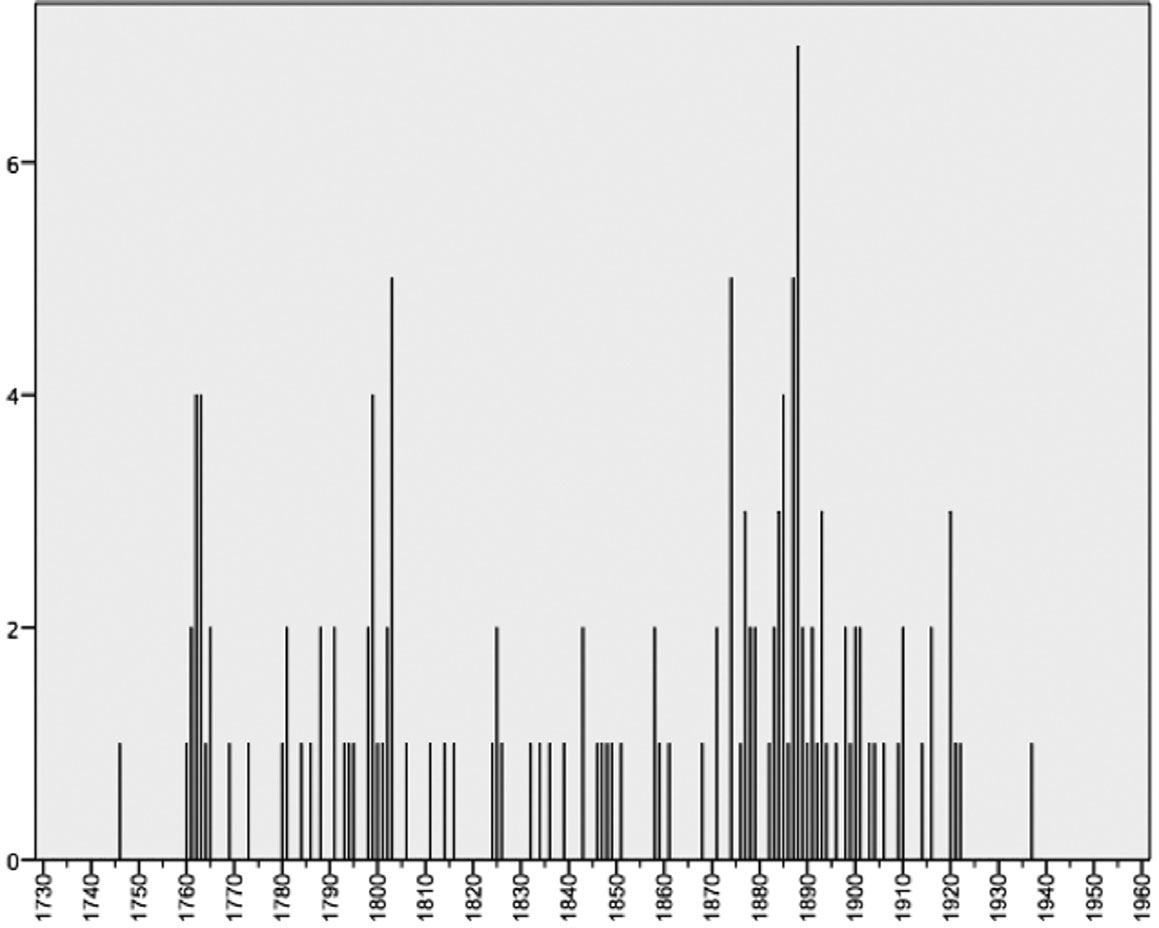

To clarify, the idea of multicentricity draws from world-systems theory that pro-

poses that the global economic system oscillates between two different phases

(Boswell 1995; Wallerstein 1980, 1989). One phase is the unicentric or hegemonic

phase. This is when the world system has a hegemon: one state enjoys a “prepon-

derance over the world economy” (Boswell 2004: 4). During this phase, there is

an unequal distribution of global economic power (with one state—the hegemon—

dominating the scene). By definition, the system is not competitive. The other phase

is multicentricity: there is more of an economic balance across the field (and hence the

former hegemons’ economic power declines relative to other states). This means that

the system is at its most competitive: unlike unicentric phases, there is no single eco-

nomic “winner.” Ultimately this multicentric phase can give way to a new unicentric

phase as one of the contenders becomes hegemonic (Wallerstein 1984, 2002).

How does this matter for imperialism? Multicentric phases—that is, when the

system was its most economically competitive—induce the most threats (economic

as well as geopolitical). Imperialism results as a state strategy to manage those threats.

The threats can be either real or imagined. They might take the direct form of rival

powers taking territory, but they need not take such a form. States do not respond

to rival powers’ territorial advances in a one-to-one fashion. Instead, multicentricity

entails a pervasive sense of insecurity: a climate of threat attendant with economically

competitive environments. Imperialism is the result.

But exactly why and how? Multicentric structures cause imperialism for two rea-

sons. First, in multicentric periods, state rulers face enhanced pressure for expansion

from capitalists. By definition, during multicentric periods, capitalists operating in or who have an interest in overseas environments face consistent economic challenges

from competitors. Rival firms are poised to undercut capitalists’ market share or areas

of investment. Even domestic capitalists face these threats if the growing power of

rivals threatens to invade domestic markets. Therefore, in this situation, capitalists

are more likely to prefer direct colonial control by their home state because such

control might (a) offer security for their own operations overseas in a competitive

environment and (b) prevent rival firms from taking those territories to expand their

power. Accordingly, during multicentric phases, capitalists will most likely pressure

the state to seize colonies for economic security and defense.

Second, the state feels more threatened during multicentric phases. Even if capitalists do try to secure their economic interests through imperialism, it cannot be

assumed that the state will respond affirmatively. So why might the state be inter-

ested in annexing territory? The answer is capital and containment. The first refers

to revenue: states need resources to function. This means the state has an interest in

imperialism that coincidentally converges with the interests of capital: states take new

territory because it helps increase trade, which might help capitalists, but the new trade

is taxable or might spur economic growth that in turn provides more taxable revenue

(see also Abernathy 2000: 206–13; Boswell 1989). In benefiting capitalists through

imperialism, state rulers can benefit themselves. The second interest, containment,

refers to security. States might expand in order to protect the integrity of their own

borders (including the borders of preexisting colonial territory) against threats from

other states. Colonies can help protect state borders and serve as nodal points in a

military defense network. Annexing territory can also help prevent the growth or

threat of rival states, keeping military opponents at bay. This interest in containment

even merges with the states’ interest in capital: additional colonies might help protect

existing overseas trade networks and production facilities or even promote them.

The state’s interests in imperialism are heightened during multicentric phases: that

is, periods of global economic competition. As increased interfirm international com-

petition during multicentric periods threatens capitalists’ trade, so too does it threaten

state revenue. More competition means more threats to taxable trade and economic

growth. The state will thus seize new colonies to meet its own revenue imperatives

while also meeting the interests of capitalist allies. Furthermore, multicentric periods

enhance not just economic threats but also perceived geopolitical threats. As some

states rise in economic strength, other states (including the rising or falling hegemon)

will fear that the new upstarts will convert their economic strength to geopolitical and

military strength. Annexation for geopolitical security becomes more likely in this

situation. In short, during multicentric periods, not only do capitalists pressure the

state to colonize, but also the state is most likely to succumb to those pressures out

of its own interests.

All of this, however, refers to multicentric phases of the world system. What

about unicentric (or hegemonic) phases? If multicentric periods increase threats to

the imperatives of capital and containment and thereby lead to heightened imperial-

ism, unicentric/hegemonic periods lessen them, and hence reduce imperialism. First,

when the hegemonic state enjoys a relative preponderance over the world economy, interfirm competition is limited and so firms enjoy a comparative advantage. There-

fore, capitalists will be less likely to pressure the state to seize more territories. Because

they already enjoy relative economic success, they prefer free markets. Second, even

if some capitalists do pressure the state to take colonies for mercantilist privileges,

the state is less likely to respond affirmatively. Because the state faces minimal com-

petition, threats to the states’ revenue sources are likewise minimized. And because

other states are economically much weaker, they pose less military threats. In short,

unicentric periods render the hegemonic state more secure than otherwise. This is not

to say that peace prevails or that threats do not exist. But relative to other historical

periods, the threats are less: in perception if not in reality. And while these threats

might be met with direct military action, they are not as serious as to demand costly

military intervention and costly annexation. In short, as hegemonic capitalists enjoy

an economic advantage during unicentric periods, the state enjoys a comparative

geopolitical advantage during unicentric periods too. Therefore, both capitalists and

state managers are more likely to pursue their interests through diplomacy or treaties

rather than through the coercive and costly hand of colonialism. Hegemons, exactly

because they are hegemonic, prefer the status quo—nothing broken, nothing to fix

(see figure 2).

Estimating British Imperialism

The relative explanatory power of the structural-competition approach can be assessed

using time-series data. As noted, existing studies have not adjudicated the different

explanations for British imperialism; they tend to focus upon short time periods or sin-

gle cases of colonial annexation. Time-series data on acts of British colonialism over

centuries can help here (e.g., Boswell 1989; Ostrom 1990; Pollins and Murran 1999).

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is an event count: the number of territories (or “colonies”)

annexed by the British state per year. This comes from Stewart’s encyclopedia (1996)

of British colonies, which offers more robust data than might be typically used, such as

Henige’s list (1970). Henige lists colonial governors appointed by all states. Scholars

have used Henige’s data as a rough measure of the year when a new colony was

annexed, corresponding with the year when the first colonial governor was appointed.

But this data does not differentiate between territories that are newly acquired and

territories that are renamed or reorganized. Stewart’s list, which provides a brief

historical overview regarding each annexation, enables one to ascertain the year when

Britain first annexed a territory and treat it as a single event. Table 1 gives descriptive

statistics of the dependent variable. Figure 1 plots the variable over time.

The question is: What explains these dynamics? Existing theories have different

answers that can be tested through the following independent variables.

[figure 2]

Hobson-Lenin Thesis

According to the Hobson-Lenin thesis, British imperialism was driven by financiers

seeking new outlets for investment. To capture this I enter the amount of British capital

exported abroad: the net outflow of British savings into foreign assets. Economic

historians offer good information for this variable in the form of the overall balance on

the current account. This represents annual net foreign investment from Britain minus

annual additions to bullion reserves. Economic historians typically use it to measure

British overseas investment (Tiberi 2005). Using this measure, the hypothesis is that

the greater the amount of foreign investment, the more colonies Britain subsequently

took to protect those investments. Alternatively one might argue the reverse: the state

takes colonies first, investment follows. But this is not the Hobson-Lenin thesis. In

their theory, financial investment comes first and annexation follows. Both Hobson

and Lenin suggest the new imperialism was driven by financiers who had already

invested abroad and then pressured the state to colonize afterward (Brewer 1990: 73;

Eckstein 1991: 303–5; Hobson 1902: 63). In any case, the tests correct for this also,

as discussed in the following text.

Militant Nationalism

I test the Spencer-Schumpeter alternative thesis that militant nationalism drove im-

perialism by using two measures. The first is the proportion of the population in

the armed forces. This is a useful measure of Spencer and Schumpeter’s concept of

a warlike culture or “re-barbarization.” According to Spencer and Schumpeter, one

key element of re-barbarization is the spread of militaristic attitudes and practices

throughout the nation. The proportion of the population in the armed forces is a good

measure of this, for Spencer referred to the growth of the military as an indicator

of the growth of military culture throughout British society (1902: 113). While the

proportion of the population in the entire armed forces (both the army and navy) would

be the ideal measure, especially considering the prominence of the British Navy, that

data is only available from 1815 onward. The proportion of the population in the

army is used instead because data is available for much further back in time. This

should not be problematic; the available data show that army and navy membership

is significantly correlated (Pearson r = .471 sig. at .001).

The other aspect of the Spencer-Schumpeter thesis is nationalism; or more precisely,

“jingoism” in the popular press. To capture this, the number of articles in The London

Times with the phrase “our empire” is used. The Times was the main periodical for

the social groups that are identified by Spencer as the leading jingoists: educated

upper classes, journalists, and statesmen. It is probably the only quantifiable source

capturing the discursive consciousness of those groups. The phrase “our empire” is

selected because scholars agree that the term empire during the late eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries was a mark of pride and distinction. It was not primarily used

to refer to Britain’s overseas colonies but to Britain’s strength and power (Koebner

and Schmidt 1964: 33–46; Portner 2004). It is reasonable to suggest that the more the phrase “our empire” was uttered among the leading classes, the more jingoist they

were. The hypothesis: the greater the proportion of articles using “our empire” and/or

the higher the proportion of the population in the armed forces, the more colonies

were taken.

[END OF EXTRACT]